We’re pretending to see what the future will hold…

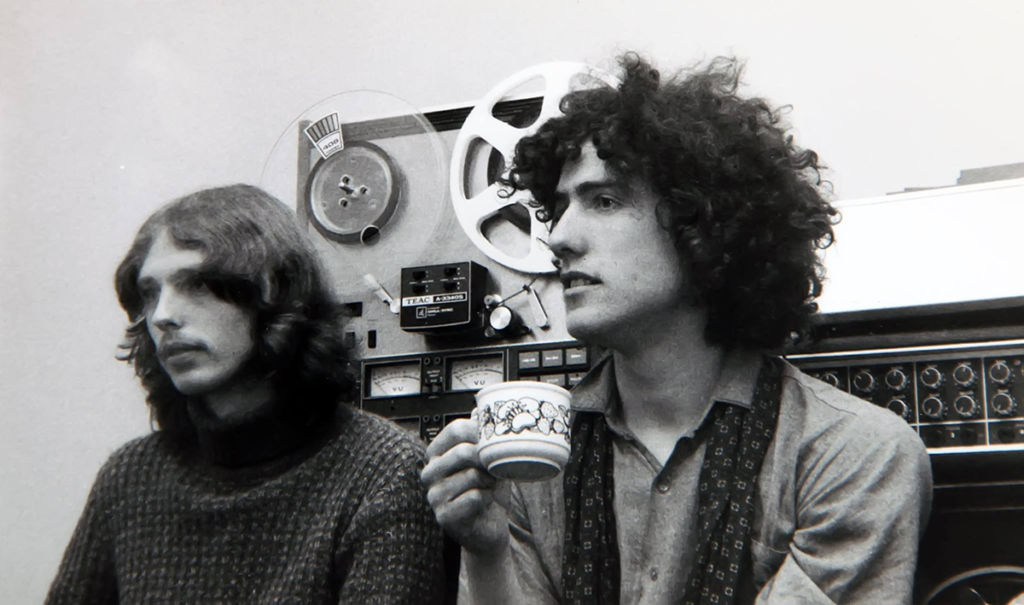

This month marks the 40th Anniversary of OMD’s debut album release. Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark was a landmark album that not only demonstrated that the duo of Andy McCluskey and Paul Humphreys were no flash in the pan act, but also became one of synth pop’s most iconic albums. It’s also one of the most visually striking records courtesy of Ben Kelly and Peter Saville’s design chops. The die-cut sleeve renders the album as an art icon as much as a collection of music.

But prior to the album arriving, OMD were not necessarily in the most promising of places. Although the release of their debut single ‘Electricity’ on Manchester’s Factory label had garnered some critical acclaim, there was no master plan in place for where to go next. A Factory tour saw the duo share the bill with the likes of Joy Division and A Certain Ratio, which again showcased OMD’s ability to be a dynamic live act. But once that tour had concluded, Paul Humphreys found himself back on the dole while Andy McCluskey had suffered the loss of his bass guitar (which he had owned since he was sixteen) when it was stolen at OMD’s first London performance at Acklam Hall.

But OMD’s story took an upward turn when they came up on the radar of Carol Wilson, who at that time was managing director of Virgin Music. The band’s fortunate collaboration with Peter Saville on the sleeve design for ‘Electricity’ (which was created using thermographic ink, creating a ‘black on black’ effect) meant that the single stood out from the other 7″ releases that were coming in every week to Virgin’s offices. Not only did its distinctive design catch Wilson’s eye, but the sleeve also had a contact telephone number.

Swayed by ‘Electricity’ (and later by witnessing OMD in live performance) Carol Wilson swiftly put a contract forward to the fledgling OMD for the DinDisc label. both Andy and Paul were stunned by the idea – and particularly the numbers that the contract was presenting. This included a £30,000 advance for the first album, which when added to the other figures in the contract presented a very serious sum of money. Suddenly, they were moving onto a larger stage and had to consider if music as a career could actually be a possibility.

“In the summer of ’79 we still couldn’t believe that Factory Records had wanted to release our first single ‘Electricity’” recalled Andy, “and although obviously that had done well, and we’d been asked to support Gary Numan on his tour in the Autumn of ’79, we didn’t still really take the whole of the music industry terribly seriously. We just couldn’t believe that doors kept opening for us without us even trying to request entry. And signing to DinDisc just seemed to be another, to us, lucky break.”

Conferring with their then-manager Paul Collister, the duo were still sceptical about the idea but reasoned that they could sink their advance into the creation of their own studio. On that basis, if the music flopped then at least they would have a studio to show for it rather than run up an expensive series of bills hiring studio time to record their debut album.

The end result saw band and manager take over an upper floor in the heart of Liverpool’s musical legacy (it was a stone’s throw from Eric’s Club and Probe Records – both legendary musical landmarks) to convert into a working space. But they were surprised by how much work was involved in the building of the studio, which meant that on its completion they only had three weeks to record the album (DinDisc had already announced a February 1980 release date).

Meanwhile, a reissued ‘Electricity’ (and later follow-up single ‘Red Frame/White Light’) hadn’t exactly troubled the upper end of the charts. Putting aside worries about the success of the venture, Andy and Paul had at least completed the building of their studio which they named ‘The Gramophone Suite’. They also wrote two new songs as potentials for the album (‘The Messerschmitt Twins’ and ‘Pretending To See The Future’, respectively).

Previously, Andy and Paul had already embarked on a road of musical experimentation outside of The Id (the Wirral-based collective where they had honed their musical talents), but had kept their compositions to themselves. Dubbing themselves as VCL XI (the name inspired by a valve number on the back of Kraftwerk’s Radio-Activity album) a lot of the strange material they worked on utilised sampled dialogue and sounds from TV programmes. Among these compositions was a track actually titled ‘Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark’, which combined sounds of classical music and war noises along with the sound of radio interference.

Many of these unusual ideas were cast aside prior to the first album being recorded, with the exception of ‘Dancing’, which remains as one of OMD’s odder songs. ‘VCL XI’ (another experimental composition named after their earlier incarnation) was held over for the Organisation album, while some of their other abstract pieces, such as ‘Once When I Was Six’, were issued with a free EP that came with initial copies of that album. Instead, the focus was on the more traditional songwriting method employed by the songs that they had performed with The Id. Certainly tracks such as ‘Electricity’, ‘Messages’ and ‘Julia’s Song’ had at least benefited from being road-tested.

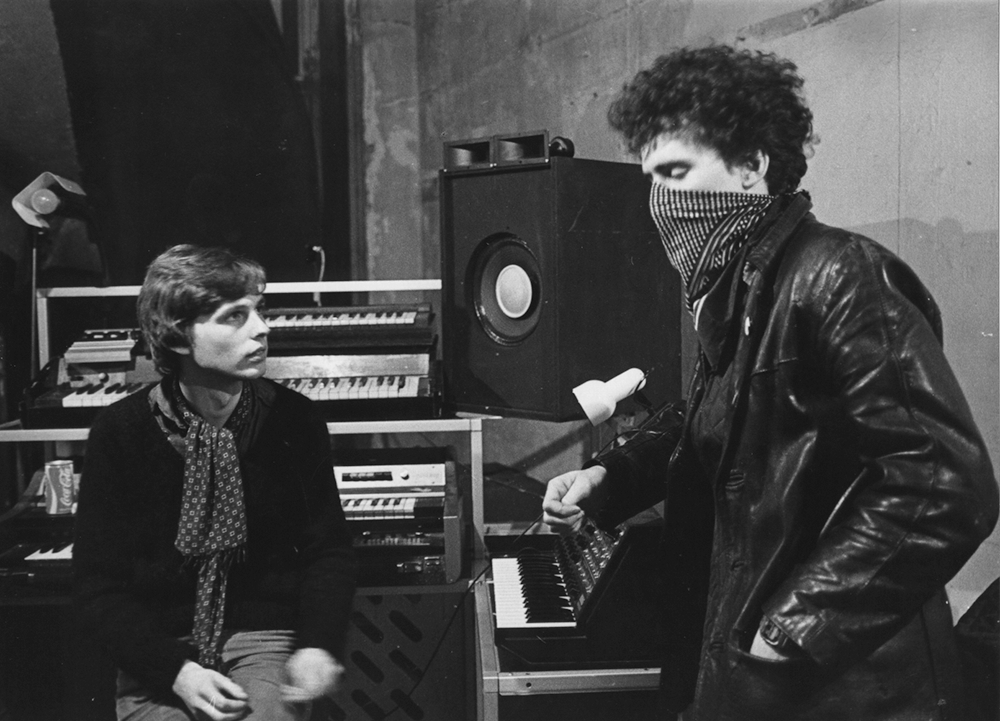

For a band that have since been lauded as synth pop pioneers, it’s ironic that at this time their synth arsenal was oddly lacking. For live shows, they were often borrowing equipment, such as fellow electronic act Dalek I Love You’s Kawai synth or borrowing a Roland SH1000 from the local college.

OMD’s foundation sound was actually cultivated from their use of the Vox Jaguar organ and a Selmer Pianotron (it’s the Pianotron that provides the lead melody on ‘Electricity’). But things changed significantly when they invested in a Korg M500 Micro-Preset (which was bought via a mail order catalogue and paid off in instalments!). It’s the Korg that provides the evocative reedy melody on ‘Almost’ for instance, but it was also used for ‘Messages’ – both the album version and the single version use the Korg for their (very different) intros.

Not that this lack of equipment held OMD back. The pair’s knack for ingenuity meant that they could pull some dynamic and often heartfelt tunes from their skimpy gear. The final Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark album certainly has a ‘garage punk’ sensibility about it. Or as Paul Humphreys described it: “Sometimes beautiful and sometimes a little naive, but then that really is a big part of its charm!”

“In retrospect we might have had a more polished album if we had gone elsewhere” muses Paul Collister on the same topic, “and perhaps more chart success earlier on, but mostly I was satisfied with the album. I really like the rough edge it has. My production style, and also my poor studio engineering, created a rough ‘in your face’ edge to the music. Andy and Paul added more refinement.”

Although at this stage OMD was still a distinct two-man operation, some third parties came on board to assist with some of the recording for the album. Previous Id cohort Mal Holmes was on percussion duties for ‘Julia’s Song’, Martin Cooper added a distinctive sax line to ‘Mystereality’ and Dave Fairbairn lent some guitar to both ‘Messages’ and ‘Julia’s Song’.

Among the material that made the final cut was the evocative ‘Almost’, which had previously graced ‘Electricity’ on the single’s B-side. Its melancholic melody provided one of OMITD’s warmer moments, a tune that became one of Martin Cooper’s favourite songs (“It just still sends shivers up my spine”).

‘Almost’ had been inspired by The Teardrop Explodes’ song ‘Camera, Camera’, which featured the line “I see a red car, I see a green car”. The phrase lodged in Andy’s mind and he reworked the idea of travelling to see a loved one by car.

‘Red Frame/White Light’, meanwhile, drew influence from a telephone box used by the band in Meols. The telephone number in the lyrics is the actual number of the phone box. OMD fans would often ring the number expecting to speak to Andy and Paul, forgetting to also dial the Liverpool area code. Subsequently, irate people around the country kept receiving calls from over-enthusiastic OMD fans!

The perky composition had the working title of ‘Telephone Song’ in its earliest incarnation, although the band drew from The Velvet Underground’s White Light/White Heat album for its eventual title. It also utilises a Roland CR-78 drum machine (using the ‘Rhumba’ beat setting), a piece of kit that later provided the percussion to OMD’s classic hit ‘Enola Gay’.

BUY NOW

https://amzn.to/4cyacc4

While ‘Enola Gay’ wouldn’t feature on this particular record, the use of war as either a metaphor or a direct influence is all over the OMITD album. Notably, ‘Bunker Soldiers’ emerged as an anti-war commentary (“your propaganda is losing appeal”), something which would later be a returning theme for OMD. The song features a chorus that actually spells out the title ‘BUNKER SOLDIERS’ as random letters and the same letters translated into numbers. These were then sung by Andy and Paul giving the song a boisterous dynamic delivery.

‘Messages’ hardly needs an introduction, being the OMD composition that finally gave the band the wider public exposure that would really put them on the map. But here, the album version eschews the polished tones of the hit single for a raw slice of electropop. It’s a version that Mal Holmes still has a fondness for: “I think the original version of ‘Messages’ has just got real magic and real charm to it.”

‘The Messerschmitt Twins’ takes its title from a nickname for Andy and Paul. The phrase popped into Andy’s head during the night prompting him to write a song about it. It was actually while researching Messerschmitts that Andy spotted a reference to the Enola Gay mission, leading to fresh inspiration.

Elsewhere, the aforementioned ‘Dancing’ was an experimental piece whose unusual off-kilter sound was created using Dalek I Love You’s Kawai synth.

‘Pretending To See The Future’ perhaps best illustrated Andy and Paul’s frustration with being involved in the music industry to begin with. The lyrics offer up a sense of bewilderment at their fortunes, while also throwing some cynical commentary on music as a “product” which is repeated each year with “a very similar sound.”

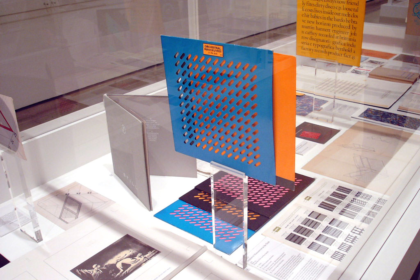

But outside of the music, it’s the sleeve design for OMITD that makes it stand out. Conceived by Ben Kelly and Peter Saville, the ‘lozenge’ concept not only gave OMD a distinctive brand, but turned the album into a work of art. Ben Kelly had originally floated the idea of using perforated sheet steel as a sleeve design idea, having already used the same material as part of the design for a boutique in Covent Garden.

The original sleeve design featured a blue outer sleeve combined with an orange inner with a 12 x 12 die-cut grid. When Peter Saville realised that the printers could change the colour combinations every 10,000 copies at no extra cost he opted for a black/pink variation. When DinDisc realised that OMD fans were buying the second version they asked for a third design.

Saville also rectified a problem with the earlier design (where the inner sleeve could fall out) by later reducing the 12 x 12 grid scheme to a 10 x 10 one.

But the striking design idea came at a cost, as Andy recalled: “The only dilemma for us, of course, was that not understanding how the royalty system worked, we had a sleeve that was costing us so much to manufacture that for every record we sold we were barely earning a penny!”

After the die-cut sleeves were exhausted they were replaced with a standard sleeve. These utilised a simpler (although still bold) design that had been used for cassette releases of the album.

As an album, OMITD drew critical praise from a variety of commentators. “A triumph of self-sufficiency and self-discipline” suggested Paul Morley in the NME. While Sounds declared the album in similarly glowing terms: “It’s a debut musical statement to be proud of.”

Back in 2003, OMITD was remastered and reissued with additional material. As part of the reissue project, Paul Browne conducted new interviews with the band members to assess their thoughts on the album as part of the content for the sleeve notes. You can read those interviews in full below.