It’s a long long way…

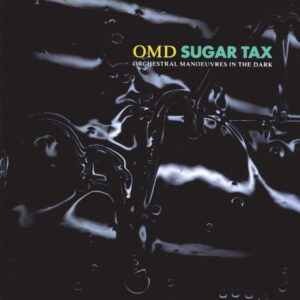

Thirty years ago, OMD scored back-to-back top 10 hit singles for the first time since their commercial and artistic peak in the early 1980s, but it was a success that was achieved without three of the legendary synth-pop act’s original members. Barry Page tells the story of OMD’s hit album Sugar Tax and one of the unlikeliest comebacks of the 1990s.

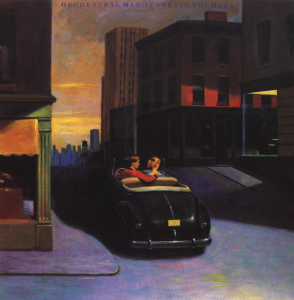

In the spring of 1988, Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark released their biggest selling album to date, a career retrospective that rounded up classic singles from the band’s imperial phase in the early 1980s – namely, ‘Messages’, ‘Enola Gay’, ‘Souvenir’, ‘Joan of Arc’ and ‘Maid of Orleans’ – plus more recent hits such as ‘Locomotion’, ‘Talking Loud and Clear’ and ‘(Forever) Live and Die’. It was only kept off the top of the charts by the debut albums from both Terence Trent D’Arby and Morrissey.

Certainly, The Best of OMD served as a timely reminder of what a great singles act the Wirral-based act were, even if the failure of then-recent singles such as ‘We Love You’ and ‘Shame’ had resulted in a slight dip in popularity in the UK. Across the big pond, however, it was a different matter and the band’s stateside popularity – largely down to the surprise success of ‘If You Leave’, which had been written to order for the movie Pretty in Pink (see feature previously) – was confirmed by a support slot on the US leg of Depeche Mode’s Music for the Masses tour. In addition, the band’s most recent single, ‘Dreaming’, had also reached the Billboard Top 20.

On the surface, there was nothing to suggest that OMD were on the verge of breaking up, and when the classic four-piece line-up of OMD – Andy McCluskey, Paul Humphreys, Martin Cooper and Malcolm Holmes – reconvened in the summer of 1988 to work on the follow-up to their most recent studio album, The Pacific Age (1986), you may have been forgiven for thinking there was some degree of excitement. Sadly, this wasn’t the case.

A Record Mirror interview with keyboardist Paul Humphreys in July 1988 papered over the cracks, intimating that the band had started work on their eighth studio album. “Last night I was working on the backing track to ‘Wild Strawberries’, which will be on the LP, until about five in the morning,” he told Tony Beard. “When I opened the shutters, the milkman was standing outside, obviously trying to get a sneak preview of the LP!” Such joviality, however, was in stark contrast to what had been happening behind the scenes over the past 12 months.

As singer Andy McCluskey later recounted to Q magazine in 2001, a poor deal they’d signed with Virgin Records at the start of their career had left them in a precarious financial situation. “We never seemed to be seeing any royalties despite selling millions of records,” he said. “The final straw was a tour supporting Depeche Mode where we got $5000 per gig, which didn’t cover our costs, and they got enough to retire on.” As it later transpired, the band owed a small fortune to Virgin, and The Best of OMD had ostensibly only been released upon the orders of their accountants, who had also advised the closure of their official fan club in February 1988. (The fan club was replaced by the OMD Information Service, which was run by Humphreys’ sister-in-law, Jan.)

The biggest problem, however, was that the band had hit something of a creative impasse. Years of touring had taken their toll as they strove to crack the lucrative US market, while the pressure to write and record a new studio album every year – as was de rigueur in the opulent 80s – had left the band burnt out. By this stage, OMD were, sonically speaking, unrecognisable from the act who had released their Kraftwerk-inspired debut single, ‘Electricity’, on the Factory label a decade earlier, and it was unclear which musical direction the band were going to take on their next album, particularly since brothers Neil and Graham Weir – who’d been on brass duties since 1984 – had now returned to their native Scotland.

By the summer of 1987, there were some early warning signs that Humphreys and McCluskey were struggling for inspiration, as they attempted to write a brand new track for The Best of OMD. “From May through June and July, we wrote and wrote and wrote,” McCluskey told the band’s fan club in 1988. “We must have written well over 20 new ideas for songs, all of which we were totally convinced were complete and utter rubbish, and the more we worried about it, the worse the songwriting block seemed to get.” The result of these sessions was the aforementioned Billboard hit, ‘Dreaming’, but it was a track the band would later disown.

One year on, the same problems would resurface, but there were other factors that would ultimately play a part in the band’s demise. Firstly, McCluskey didn’t enjoy working in Humphreys’ garage-turned-studio. “Paul’s studio was a great facility,” he told the OMD Information Service in 1990, “but ultimately it was a problem for us, because it meant if I wanted to do anything, I had to go to Paul’s house, which meant I was frustrated. I couldn’t do any of my ideas without Paul being there. I felt that a lot of what OMD was about was me having ideas, nine out of ten which were stupid and didn’t work, but occasionally I’d have a flash of something weird that worked, and I didn’t get the chance to do it.”

Secondly, Humphreys had developed a strong bond with his bandmates, Martin Cooper (keyboards and saxophone) – who’d had a hand in big hits such as ‘Souvenir’ and ‘Talking Loud and Clear’ – and Malcolm Holmes (drums). Both Cooper and Holmes felt that they had been treated like session musicians in recent years and wanted more creative and financial control going forward. Humphreys was sympathetic, and started working on song ideas with them while McCluskey wrote independently. It soon became apparent, however, that this arrangement wasn’t going to work. “I didn’t like the style of their songs,” McCluskey told Q magazine in 2001, “and I didn’t think they were very good. I just thought if these songs had to be on the album and my songs had to be done their way it would just be the end of OMD.” The idea of these disparate camps contributing a side of an album each was quickly dismissed, as was the idea of the two camps working on their separate projects before reconverging as OMD. “We just wanted to make an album outside of OMD which would have taken the best part of a year,” Humphreys told the Telegraph fanzine in 1993. “We wanted to do that and then come back to OMD and see how well it worked after that period of time, but Andy wouldn’t do that.”

THEN YOU TURN AWAY

Inevitably, the band fell apart in 1989 and McCluskey was left to lick his wounds while his erstwhile bandmates continued to work together. It had been assumed by the singer that this was a clean break and that the OMD name had been laid to rest, so it came as something of a shock when Humphreys approached him several weeks later with a surprising proposition. “Paul came back to me and said he, Martin and Malcolm wanted to continue as OMD as there were three of them and only one of me,” McCluskey explained to Record Mart & Buyer in 1998. “… I told them I’d heard the sort of music they were making and I said I wasn’t having it called OMD. I came to Virgin and said, ‘Can Paul be OMD without me?’ They said they owned the name and said they’d rather I was OMD.” Thus began a protracted dispute, which was later described, somewhat sensationally, by the Daily Star as a ‘bitter, 18-month court battle’. Humphreys held out for the best financial outcome, eventually signing over the rights to the OMD name for an undisclosed sum.

While Humphreys, Holmes and Cooper waited to be extricated from their contract with Virgin Records, they continued to demo songs for their debut album, in addition to other projects, which included some soundtrack work and a B-side, titled ‘Super 7’, for a Wirral band named Alternative Radio. Aside from its choral flourishes, the generic house instrumental was unrecognisable from the more organic and expansive material the trio – as the Listening Pool – would release on their own Telegraph Records label between 1993 and 1994.

Meanwhile, McCluskey was understandably depressed by the band’s split in 1989 and the ensuing legalities, later admitting that he spent long periods at his new house, which he would claim was haunted. (Later, it provided the lyrical inspiration for ‘Walking on Air’.) However, he was credited with co-writing and singing ‘Walk Away’, which appeared on an album, titled Merge, by the legendary producer Arthur Baker. The August release also included collaborations with Martin Fry (ABC), Al Green and Jimmy Somerville (Bronski Beat, The Communards).

It later transpired that McCluskey had also played keyboards on ‘Frenzy’, the B-side of the Lightning Seeds’ second single, ‘Joy’, which was also released that year. The Lightning Seeds were essentially a solo vehicle for Ian Broudie, who McCluskey knew from OMD’s playing days at the legendary Mathew Street club Eric’s in the late 70s – the future ‘Three Lions’ hitmaker had been a member of post-punk outfit Big in Japan, whose members included Liverpudlian luminaries such as Holly Johnson (Frankie Goes to Hollywood) and Bill Drummond (the KLF).

PRETTY IN PINK

Crucially, in 1989, McCluskey began working with bassist Lloyd Massett and drummer Stuart Kershaw, two members of a local pop/rap crossover act named Raw Unltd. Their debut single, ‘Romeo and Juliet’, released in February that year, had been recorded at a vibrant facility named the Pink Museum, where the original line-up of OMD had recently booked some studio time in a last-gasp attempt to get their eight studio album off the ground. Bedecked with fanciful, tropical foliage, the converted motor museum, off Lark Lane in Liverpool, had been opened in May 1988 by the late Hambi Haralambous, the former frontman of Hambi and the Dance, who had been signed to Virgin earlier in the decade. In January 1989, the La’s had used the studio during one of their many sessions leading up to the release of their debut album the following year, while later clients would include Oasis and Arctic Monkeys.

McCluskey had been encouraged by Haralambous to work with different musicians and Raw Unltd were a local act the studio owner was managing at the time. The fledgling band also happened to be looking for someone to produce tracks for their debut album. It was a symbiotic arrangement that looked perfect on paper, but McCluskey later labelled his production work “a complete disaster”. However, the team-up proved pivotal in reigniting the struggling songwriter’s creative spark, with both Massett and Kershaw feeding numerous song ideas to him. “They’d just come round and throw things at me, chord sequences, bass lines and rhythms,” McCluskey explained to Vox magazine in 1993. “They were prepared to give me things and just leave me to get on with. If I didn’t like them, there were no obligations, hurt pride or bruised egos. It was selfish and it was greedy, but it worked for them, because their ideas were made into finished songs on a successful LP – which helped them get their original publishing deal – and it helped me kick-start my own songwriting.”

McCluskey admitted that there was a conscious effort to use more programming, deliberately steering away from the live band sound of OMD’s previous two Stephen Hague-produced albums, Crush (1985) and The Pacific Age (1986). “The more acoustic instruments we used, the more we lost the sound of the band,” McCluskey told Music Technology magazine in 1991. “I’ll probably tell you something different in five years time, but as of now I’m convinced that the distinctive sound of OMD is the juxtaposition of the rhythm technology – samples, drum machines and bass sequences – and the emotional side of the lyrics, melody, choral and string pads that float across the top.”

However, while the sounds emanating from the Korg M1’s choral presets would, to a certain extent, transport fans back to OMD’s heyday, there was also a desire to incorporate more contemporary sounds, reflecting the proliferating number of dance and electronic acts in the charts – acts such as Bassomatic, Black Box, 808 State, the KLF and Technotronic were all on McCluskey’s musical radar during the late 80s/early 90s. One particular OMD track, ‘Resist the Sex Act’ – which currently remains unreleased – was even influenced by Lil Louis’ orgasmic club hit, ‘French Kiss’. McCluskey’s fondness for religious choral music was also evident on ‘Walk Tall’ – which was built around a sample of a recording of ‘Miserere mei, Deus’ by Gregorio Allegri – and the Enigma-inspired B-side ‘Vox Humana’, which incorporated a recording of a Hildegard von Bingen Gregorian chant, set to a Soul II Soul beat.

Originally pencilled in as the album’s first single, ‘Call My Name’ was a conscious attempt to traverse a more dance-pop-oriented terrain, as Stuart Kershaw recalled on Twitter earlier this year: “One of us said, ‘you know what? We should do a house track.’ How we laughed! Then one of us actually programmed a house beat on the HR16 [drum machine] and an Akai sampler and then cycled it. I started with [a Korg] M1 piano sound and came up with the melody section riff. Andy and I went section-by-section, creating a new sequence of chords and ended up with something that clearly inspired the Killers’ song, ‘Human’.” Eventually, ‘Call My Name’ became the fourth and final single to be released from the album, though McCluskey’s idea to incorporate Nigel Ipinson’s new piano parts – as showcased during the Sugar Tax tour – on the 7” mix was, arguably, misjudged.

MINISTRY

The initial recording of Sugar Tax was set for the spring of 1990, with Howard Gray (a former tea boy cum tape operator, who had worked on OMD’s seminal third album, Architecture and Morality) and Andy Richards producing four of the finished twelve tracks between them – McCluskey would take the reins for the remainder. Many of the song arrangements had already been worked on with Lloyd Massett and Stuart Kershaw at his rehearsal space, the Ministry, in Preston Street, as the singer confirmed to Music Technology magazine in 1991: “I had their performances recorded from the rehearsals and the songwriting. So when I actually got into the studio, it was just me and my Atari [computer], plus whoever did the singing.” Indeed, a series of female session singers were brought in, which would result in a more chart-friendly sound.

In terms of the material, it was the co-writes with Massett and Kershaw – ‘All That Glitters’, ‘Call My Name’, ‘Then You Turn Way’, ‘Walking on Air’ and ‘Walk Tall’ – that would provide the foundations of the resulting album, but, with his batteries recharged and his creative muse now reinstalled, McCluskey would write other key tracks, independently, at the Ministry. These included the plaintive ‘Was It Something I Said’. Slightly reminiscent of ‘Joan of Arc’, the song recalled the more epic and symphonic side of OMD, with McCluskey turning in the album’s most heartfelt and impassioned vocal performance. Like the closing ballad, ‘All That Glitters’, the song saw the singer reflecting on OMD’s split, offering something of an insight into his fragile mindset at the time. “A lot of the songs I’ve written are actually about Paul and I,” McCluskey told the Telegraph fanzine in 1991. “The way that the lyrics are put together might perhaps not be that obvious to people. They might sound like love songs actually, but they’re not. I think people who’ll listen to the album will realise that there are some songs on there which are really about how upset I was.” Many fans were disappointed that this cathartic showstopper wasn’t released as a single, but McCluskey claimed it wasn’t radio-friendly.

One track that definitely was ripe for the airwaves was ‘Pandora’s Box’, whose provenance went back to the early 80s. After chancing upon photographs of the silent movie actress, Louise Brooks, McCluskey began a decade-long quest to immortalise her story in song. “Her whole life story really is fascinating,” he told the band’s biographer, Johnny Waller, in 1993. “… She was courted by all the famous people in first New York and then Hollywood, and basically was so self-destructive that she threw away career opportunities like they were bad pennies. Every time something good was about to happen, she just blew it! Then she went into decline and lived in seclusion and lived the second half of her life in near-poverty.” There was something of a false dawn when McCluskey demoed ‘American Venus’ (included in 2019’s Souvenir boxset), but aside from the ‘Born in Kansas’ lyric, there was little else in common with the track that would follow.

The Ministry was also the scene of the writing of the album’s first single, ‘Sailing on the Seven Seas’, which featured a vital contribution from Stuart Kershaw. “I had gone out of my writing room in the centre of Liverpool to buy some stationery and started singing a drum pattern,” recalled McCluskey on Twitter. “I ran straight back and starting programming on my little Alesis drum box, blocked in two chords and got a lyric idea immediately. Just then, Stuart arrived and I asked him what to do in the gaps in the verse. He wrote the piano refrain from the top of his head, and suggested a chord pattern for a possible chorus.”

LETTER FROM GOD

Following McCluskey’s creative burst, there was enough material to fill two albums. Some of the outtakes were eventually used on B-sides, while others were either discarded (for example, ‘Cruel’, ‘Resist the Sex Act’ and ‘You’re Always Coming Back to Me’) or included on later albums (‘Love Theme’, whose release was held up by Barry White’s reluctance to authorise a Love Unlimited Orchestra sample, appeared on 1993’s Liberator (see previous feature), while ‘Wheels of Steel’ ended up on 2010’s hotchpotch of outtakes and newer cuts, History of Modern).

Although, there was plenty of original material in the can, McCluskey also included a version of ‘Neon Lights’ (from 1978’s The Man-Machine), which included a dreamy vocal from Christine Mellor. McCluskey had to ask Kraftwerk for permission to use the track; thus began a friendship with Karl Bartos, which would eventually lead to co-written songs such as ‘Kissing the Machine’ (1993) and ‘The Moon and the Sun’ (1996). “He graciously allowed the cover,” recalled McCluskey on Twitter. “I kept the fax he sent as it was like a letter from God!” (A decade later, ‘Neon Lights’ was also covered by Simple Minds on their album of the same. During 2009’s Graffiti Soul tour, the band were joined by McCluskey and Humphreys for a unique version of the iconic track.)

One of the tracks Virgin weren’t keen on was the novelty house track ‘Apollo XI’, but OMD had a long history of including unusual songs on their albums (see ‘Dancing’, ‘The More I See You’, ‘Crush’, ‘Southern’, etc) and McCluskey insisted on its inclusion. According to the singer, he’d found a record in a junk shop that featured dialogue from the Apollo XI moon mission. “All the samples are lifted from the record and spun in from the Akai sampler for the old Atari ST24 computer,” he wrote on Twitter. “This system was a cheap replacement for our Fairlight sampler that we bought for an astonishing 24k. These days it seems very slow and long-winded to do this, but at the time it was revolutionary to run so many triggered samples. The track sounds very early 90s techno now, but I have a soft spot for it.”

One song conspicuous by its absence, was the actual album title track. The title wasn’t, of course, a prescient reference to a future surcharge on sugar, but rather an observation from McCluskey that everything sweet has its price. He would later quip that he was being mischievous by leaving it off the album, but the truth was he wasn’t able to finish it on time, preferring instead to finish ‘Pandora’s Box’.

Originally, the album was pencilled in for a September 1990 release, but it wouldn’t appear until the new year. The series of delays, however, would work to McCluskey’s advantage as he received a tantalising offer from OMD fan and future Trainspotting director Danny Boyle to write the theme and incidental music for a 3-part BBC series called For the Greater Good, which would air in March 1991. “It was quite a challenge because I’d never done music before to fit a visual script, to get things to happen in the right place, but I enjoyed it immensely actually,” McCluskey told the BBC. “I was a bit nervous when it first came on, though!” Sadly, a licensing issue thwarted plans to include the theme on the B-side of third single ‘Then You Turn Away’, and the music still remains unreleased at the time of writing. (Danny Boyle later included ‘Enola Gay’ in the Summer Olympics’ opening ceremony in 2012.)

ANXIETY

McCluskey was understandably anxious about the release of Sugar Tax. After all, it had been nearly five years since the release of their last studio album, The Pacific Age, and not all of OMD’s contemporaries from the 80s had made a successful transition to the new decade. While the careers of the likes of Depeche Mode, Erasure and Pet Shop Boys had gone from strength to strength, others’ had floundered. Notably, Duran Duran and the Human League had delivered their weakest and most unsuccessful albums to date in Liberty and Romantic?, respectfully. This anxiety was perhaps reflected in the Sugar Tax credits, which didn’t feature a single mention of McCluskey’s name, while the images of the singer were deliberately out of focus. “I was happy to hide behind the corporate logo of OMD,” he told Record Mart & Buyer in 1998, “I wasn’t sure it was going to work out at all.”

The album inlay, which included a striking shot of an oil sculpture by experienced OMD photographer Trevor Key, was put together by a design team known as Area, comprising Cara Gallardo and Richard Smith, who had both previously worked for Peter Saville Associates. “We had sent our book to Virgin Records and the art department arranged a meeting for us with Andy McCluskey,” explained Smith to Classic Pop in 2018. “We were able to trade ‘war stories’ about working with Peter Saville and we bonded over our memories. The image for Sugar Tax was based on an invitation we created for a London art gallery show. The artist used oil in his work to create striking images and Andy loved it. There was no one else I knew who could shoot the image other than Trevor and that final shot used dish detergent on Plexiglas.”

SEVEN SEAS

When the album was eventually released, in May 1991, it rocketed to an impressive No.5 on its first week, following the extraordinary success of ‘Sailing on the Seven Seas’. The band’s noisiest and most offbeat single since 1983’s ‘Genetic Engineering’ featured huge glam rock-style drums, a cheesy Casio keyboard solo and power chords, courtesy of local guitarist Stewart Boyle (a future member of the Christians). Crucially, though, the song had a killer chorus, and even Sounds magazine would concede that it was ‘embarrassingly catchy’. Something of a slow burner, the single entered the charts at a lowly No.66, before steadily climbing to No.3, thereby emulating the peak position of ‘Souvenir’ a decade earlier.

There was a further Top 10 hit with ‘Pandora’s Box’, too. More traditionally structured than its predecessor, its chart performance was boosted both by an appearance on Wogan and an eye-catching video that interpolated original footage from Brooks’ Pandora’s Box movie (not dissimilar to the promo clip for the Lotus Eaters’ ‘It Hurts’ single in 1985). ‘OMD this week don’t know if they are a jovial Hazell Dean group or some wistful Enoesque melancholy merchants,’ wrote the NME. ‘It is this that gives them their force, their occupation of the dichotomous territories between art and pop.’

An accompanying two-legged tour would complete an extraordinary comeback. It was Pink Museum owner Hambi Haralambous who would play a key role in the assembly of McCluskey’s new live band, with two members later playing key roles during OMD’s career in the 90s. Haralambous had put the word out that the band were looking for a keyboard player, a call which was answered by Nigel Ipinson from the Rebel MC’s band. He also introduced McCluskey to drummer Abe Juckes (a future director on Coronation Street) and keyboardist Phil Coxon, a former member of the Real People who had done some engineering on the Sugar Tax album and its attendant title cut, plus a series of (uncredited) single remixes. (Raw Unltd had actually been scheduled to support OMD on the second leg of the tour, but this never materialised as the band only released one more single, ‘In My Heart’, before splitting up.)

BUY NOW

https://amzn.to/3LlS4Xa

In terms of the press reaction to the album, the reviews were mixed, but this wasn’t anything new in OMD’s career. Writing for Q magazine, Paul Davies called Sugar Tax ‘an unflappable album of quality songs which re-establishes their credentials as masters of synthesized melancholia and dreamy pop songs’, while NME’s Andrew Collins labelled it a ‘deft exercise in short-range synthesiser pop that, for the most part, flutters along on a criminally simplistic vibe with all but a low-rent beatbox and a well-depressed instant choir button to perk it up.’ However, Vox magazine weren’t as impressed. ‘Sugar Tax benefits from a smooth production and clearly McCluskey is trying to write an LP with an emotional variety,’ wrote Steve Malins. ‘Furthermore, his conventional song structures have stripped out the needless gimmicks of old OMD albums, but McCluskey’s voice is limited, his lyrics unmemorable and his songwriting lacks any lasting impact.’

Regardless of the reviews and the tepid sales of further single releases, Sugar Tax – which, according to a recent tweet from McCluskey, is set for an expanded reissue – would eventually become OMD’s most successful studio album. “I’m pleased for his success,” Paul Humphreys told the Telegraph fanzine in 1993. “I’m also pleased about the OMD name still existing. I’m pleased that the name just didn’t die completely, because we worked damn hard for 12 years to make OMD a household name.”

OMD’s career would, of course, take several twists and turns over the ensuing years, but Sugar Tax remains an important album in the back catalogue and a milestone in the band’s career, with ‘Sailing on the Seven Seas’ and ‘Pandora’s Box’ immovable songs in the reformed synth-pop pioneers’ live sets. For Andy McCluskey, it remains a sweet victory.

Thanks to Andy McCluskey, Paul Browne and Jan Humphreys.

This feature originally featured on The Electricity Club