In 1989, the classic four-piece line-up of Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark split up. Following a well-publicised legal tussle, singer Andy McCluskey took the OMD name, while the remaining members formed The Listening Pool. Barry Page tells the story.

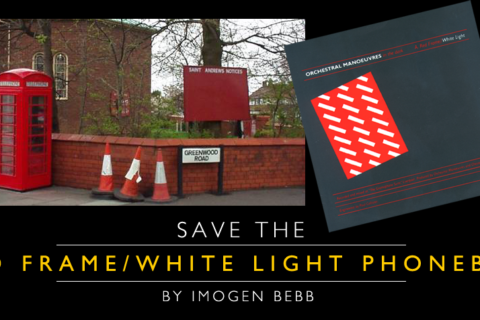

In the spring of 1988, OMD released their biggest selling album to date, a career retrospective that rounded up most of the band’s hit singles, plus a few near misses – it was only kept off the top of the charts by the debut albums from both Morrissey and Terence Trent D’Arby. Also included on The Best of OMD was the band’s brand new single, ‘Dreaming’, which would maintain their run of hit singles in the US, a marketplace they had worked so hard to crack. Such was their stateside popularity – due in part to the success of the smash hit, ‘If You Leave’, which had been written to order for the Pretty in Pink movie – they were invited to open up for Depeche Mode on the US leg of the Basildon synth-rockers’ hugely successful Music for the Masses tour, giving them the ideal opportunity to play a selection of their hits to much bigger audiences. Both the album and tour appeared to be the perfect bookend to a career that had begun a decade earlier, and when the classic four-piece line-up of OMD – Andy McCluskey, Paul Humphreys, Martin Cooper and Malcolm Holmes – reconvened in the summer of 1988, you may have been forgiven for thinking there was some degree of excitement as they prepared to work on the follow-up to The Pacific Age (1986). Sadly, this wasn’t the case.

As it would transpire, the band hadn’t even broken even on the Depeche Mode tour, while The Best of OMD had ostensibly only been released to appease the band’s accountants, who’d informed them that they owed a small fortune to their label, Virgin Records. (The tightening of the bands’ finances would also lead to the closure of the band’s official fan club.). “They would give money to us with one hand and take it back with the other,” Andy explained in 2018’s Pretending To See the Future. “They made tens of millions of pounds out of us, but I was driving a second-hand car and Paul was driving a car he’d bought in 1980 that was on its last legs. Paul had a three-bedroomed house and I had a cottage, with both of us mortgaged up to the eyeballs.”

As it would transpire, the band hadn’t even broken even on the Depeche Mode tour, while The Best of OMD had ostensibly only been released to appease the band’s accountants, who’d informed them that they owed a small fortune to their label, Virgin Records. (The tightening of the bands’ finances would also lead to the closure of the band’s official fan club.). “They would give money to us with one hand and take it back with the other,” Andy explained in 2018’s Pretending To See the Future. “They made tens of millions of pounds out of us, but I was driving a second-hand car and Paul was driving a car he’d bought in 1980 that was on its last legs. Paul had a three-bedroomed house and I had a cottage, with both of us mortgaged up to the eyeballs.”

On top of all this, the band had reached something of a creative impasse. Like many of their contemporaries that decade, they’d released a new LP almost every year and, between February 1980 and September 1986, they’d racked up an impressive seven studio albums. However, due to the demands placed upon them to tour, particularly in the US, the time allotted to write and record new material was diminishing significantly. “We were on a never-ending treadmill,” Paul told Classic Pop magazine in 2017. “We did more drugs than we should because we were compensating for the fact that we were just exhausted. Because of our shitty [record] deal, we’d tour for nine months and get back home to our manager saying, ‘You’ve got no money, you need to write an album now.’ It became so the first ten ideas we had were the next album.”

Although the band’s most recent album, The Pacific Age, had done reasonable business and spawned a transatlantic hit in ‘(Forever) Live and Die’, both Andy and Paul agreed that the album had been rushed, and there had also been some friction with Virgin over the choice of follow-up singles. Following the failure of ‘We Love You’ to reach the all-important Top 40, the band pushed for the release of a re-recorded version of ‘Stay (The Black Rose and the Universal Wheel)’, but the label instead bankrolled a new, Rhett Davies-produced version of ‘Shame’, which would also stiff in the spring of 1987.

Matters weren’t about to improve when Andy and Paul entered the studio in May 1987 to record a brand-new track for The Best of OMD. During the sessions that would eventually produce the somewhat contrived ‘Dreaming’, it had become obvious that the band’s creative well had run dry. “From May through June and July, we wrote and wrote and wrote,” Andy told the band’s fan club in 1988. “We must have written well over twenty new ideas for songs, all of which we were totally convinced were complete and utter rubbish, and the more we worried about it, the worse the songwriting block seemed to get.” Although they would later regret its release, the single did at least give them another Billboard hit – peaking at No.16 in May 1988 – but it twice failed to reach the Top 40 in the UK (in January and June), despite a high-profile TV appearance on Wogan.

WILD STRAWBERRIES

A light-hearted interview Paul gave to Record Mirror in July 1988 papered over the cracks, and the keyboardist intimated that the band had started recording their next album – even divulging one of the song’s titles, ‘Wild Strawberries’ – but there were some definite problems behind the scenes.

Firstly, Andy didn’t enjoy working in Paul’s converted garage, as he confirmed to the OMD Information Service in 1990: “Paul’s studio was a great facility, but ultimately it was a problem for us, because it meant if I wanted to do anything, I had to go to Paul’s house, which meant I was frustrated. I couldn’t do any of my ideas without Paul being there. I felt that a lot of what OMD was about was me having ideas, nine out of ten which were stupid and didn’t work, but occasionally I’d have a flash of something weird that worked, and I didn’t get the chance to do it.”

Secondly, Andy and Paul – who had been at the creative heart of the band since its inception a decade earlier – had drifted apart as songwriters, and the problems they’d encountered during the sessions that spawned ‘Dreaming’ the previous year had resurfaced. “Andy wanted to go on with me sitting at the keyboards playing loads of parts and he was picking out what he liked,” Paul explained to the OMD Information Service in 1990, “but it was getting to the stage that what he picked out, I liked too. I could really pick it out myself. I was always sitting behind at night and developing my own chord sequences. Andy’s great strength is his lyrics and vocal tunes. He had really interesting lyrics and I really like them, so the combination of his words on top of my chords and backing tracks made OMD, and that was in the good days of OMD. But in the end, I didn’t like what he was saying in his lyrics any more. What he was contributing, I wasn’t liking. I wanted to develop the music further than I was able to.”

Additionally, Paul had recently purchased a second home in the Hollywood Hills and wanted to start a family with his American wife, Maureen. Unlike Andy, who enjoyed life on the road, Paul wasn’t keen to get back on the touring horse anytime soon. “I’d been married for ten years,” he told Vox magazine in 1993, “and I didn’t have any kids, because I didn’t want to be a father who just sees his kids for a few weeks of the year.”

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

By now, Paul was gravitating towards his bandmates, Martin and Malcolm, who were disillusioned with the poor financial returns from life in a supposedly successful pop band. Malcolm, in particular, felt like he was being treated like a session musician. “I’d worked my ass off for 75 quid a week for years in a band that sold millions of records and had nothing to show for it,” the drummer wrote on his website years later. “I’d had enough of being last on the list and bottom of the food chain.” Additionally, the pair also felt that they had more to contribute, creatively. “We’re not on this ego trip or anything,” Malcolm told the Telegraph fanzine in 1990. “I think that Andy thought that’s what we were about, but we just wanted to have our piece of the action at the end of the day. We wanted, creatively, to be more involved in whatever we were going to do.” Certainly, Martin had plenty to offer. Not only had the multi-instrumentalist worked on two soundtrack albums with Dave Hughes, whom he’d replaced as OMD’s second keyboardist in 1980 – Hearts and Armour (1983) and C.H.U.D. (1984) – he’d also had a hand in big hits such as ‘Souvenir’ (1981), ‘Talking Loud and Clear’ (1984) and ‘If You Leave’ (1986).

While Paul, Martin and Malcolm worked on new material together, Andy wrote independently, but it soon became apparent that this arrangement wasn’t go to work in the long term. The idea of the two disparate camps taking one side of an album each was ruled out, as was the idea of both parties working on their own projects, before reconverging as OMD. This was something that had worked for Duran Duran in 1985 with the Birmingham band splintering into the art-pop of Arcadia and the more rock-oriented Power Station, but, again, this idea was discounted. “We just wanted to make an album outside of OMD which would have taken the best part of a year,” Paul told the Telegraph fanzine in 1993. “We wanted to do that and then come back to OMD and see how well it worked after that period of time, but Andy wouldn’t do that.”

Despite one last throw of the dice, with the band booking a final session at the Pink Museum studio in Liverpool, OMD officially split up in 1989. Andy was left to lick his wounds – later pouring his heart into cathartic pieces such as ‘All That Glitters’ and ‘Was It Something I Said? – while his erstwhile bandmates continued to work together. As for the OMD name, it had been assumed that this had been laid to rest, but things were about to get ugly. “I didn’t want anyone to be OMD,” Andy told Vox magazine in 1993, “but Paul had come back about three months after we split and said, ‘Listen, I’ve talked to my lawyer and he says the name has a value and one of us should keep it. Since there’s three of us and one of you, I think we should have it’. I hadn’t thought about it, but my knee-jerk response, basically, was ‘over my dead body’.”

Despite the numerical advantage, Virgin agreed with Andy that it was his voice that the public associated with OMD, and, following a protracted legal battle that was somewhat sensationalised in the tabloid press, Paul eventually signed over the name for an undisclosed sum. While Andy began preliminary work on 1991’s Sugar Tax album with local musicians Stuart Kershaw and Lloyd Massett (from the pop/rap act, Raw Unltd), Paul, Martin and Malcolm worked on the demos that would form the foundations of their debut album. Whilst much of the writing was done, collaboratively, at Paul’s home studio, both Martin and Malcolm brought in ideas they’d worked on at home. “All our songs start from a basic chord progression, often written on the piano,” Paul explained to Music Technology in 1993. “We never set out to write a song on a particular day; ideas are brought into the studio, and everybody can respond or not once there’s a starting point. OMD always worked that way.”

THERE’S NO TURNING BACK

As the trio waited to be extricated from their contract with Virgin, they continued to demo songs for their debut album, as well as working with other local acts such as Alternative Radio (for the B-side of their ‘Fallout’ single, released in 1990, the band collaborated on ‘Super 7’, a generic house instrumental). Additionally, there was some low-key TV soundtrack work, which included the themes for a gardening programme called Dig and a late-night show called He Play, She Play and Replay, which showcased the work of up-and-coming film directors. (In the late 80s to early 90s, Malcolm also worked on the music for a series of animations by his friend, Mike Walker, including The Man with No Brakes, The Nose, Running Joke and Ricochet, with the latter including voice-over work from John Campbell, the frontman of local cult favourites It’s Immaterial, who’d scored a memorable Top 20 hit in 1986 with ‘Driving Away from Home (Jim’s Tune)’.)

During the build-up to the release in March 1991 of Andy’s comeback single, ‘Sailing on the Seven Seas’, the band finally announced that they had a name – The Listening Pool. “It’s hard to say exactly who thought of it,” Martin told the Telegraph fanzine in 1993. “We were in LA, actually, and we had been kicking about names for ages. We had this piece of paper with all sorts of words written on it, and the name just came about. It may have been me who put the two words together.”

With the legalities finalised, the band were now free to speak to other record labels. Uninterested in signing with a major, they initially signed with the iconic post-punk label, Inevitable Records, which had recently been rebooted by its co-founder, Jeremy Lewis. Something of a feeder label, it had launched the careers of China Crisis, Dead or Alive, It’s Immaterial and Pete Wylie, among others, and it seemed like a good fit for the Listening Pool – there was even a baseless rumour that the band had toyed with the idea of releasing a new version of ‘Souvenir’ as their debut single for the legendary label.

Unfortunately, the Inevitable label folded, sending the band back to square one. Craving an independent set-up, they decided to start their own Telegraph Records label (not to be confused with the fictitious Virgin imprint that had released Dazzle Ships in 1983). Owning their own label would work to the band’s advantage, meaning they could now work at their own pace, no longer bound by the major label deadlines that had stunted their creativity as members of OMD. “Ultimately, we wanted to be in control of absolutely every part of what we’re doing,” Paul told Music Technology magazine in 1993. “Having our own label always appealed to us; we really enjoyed the time we were on Factory Records – a small set-up, but small set-ups can keep control if you use the distribution network properly and get the right licensing deals.”

Whilst the label had primarily been set up as a means of releasing the Listening Pool’s debut album, the band also signed other acts, including China Crisis and Thomas Lang, who would release the albums Acoustically Yours (1995) and Versions (1996), respectively. They also signed the Lotus Eaters’ Peter Coyle, with a view to releasing Simple Harmonic Motion by Pure Journey, Coyle’s second collaborative album with Andy Stevenson. “It contained samples and, unfortunately, we couldn’t get clearance for them,” says Malcolm. “This meant the album had to be shelved and we couldn’t release it, which was such a shame.” The label would also delve into the classical music market in 1996, releasing Debussy and Fauré: Piano Duets by sisters Nicola and Alexandra Bibby, who is Martin’s wife.

SOMEBODY SOMEWHERE

Although Paul, Martin and Malcolm had started working on material for their splinter group in 1988, their debut album, Still Life, wouldn’t appear until 1994 (by which time, Andy’s solo incarnation of OMD had already released two albums: Sugar Tax and Liberator). Whilst the delay was partly down to the legal problems the fledgling act had endured since OMD’s official split in 1989, the fact that Paul was now dividing his time between the Wirral and LA also meant that there was limited time for him to meet up with his bandmates. Understandably, there was also an extended break when his daughter, Madeline, was born in 1991.

In terms of their musical direction, whilst Andy would look to OMD’s past for inspiration, combining choral effects with more contemporary rhythms, Paul, Martin and Malcolm were intent on pursuing a more expansive sound, influenced by the likes of Peter Gabriel, Daniel Lanois and Robbie Robertson. “We’ve been doing what we felt OMD should have done two or three years ago, developing a new sound, but one which retains the essence of OMD in a more exciting format,” Paul told the OMD Information Service in 1990. “Our music has an atmosphere to it that I felt OMD started to lose, particularly on The Pacific Age. Our earlier stuff has an emotion and a passion, an evocative sound to it which I think we lost.”

In the midst of the band’s recording sessions, there was some concern that Paul’s vocals weren’t strong enough, this despite the fact that he’d previously taken the lead on many of OMD’s songs (‘Promise’, ‘Souvenir’ ‘Never Turn Away’, ‘Secret’, etc). Although he received plenty of encouragement from Martin and Malcolm, the band did consider bringing in an outsider singer, but in the end there was something of a compromise when they brought in local musician Thomas Lang for the wistful ‘Wild Strawberries’ and Londoner Paul Roberts (who had replaced Hugh Cornwell as lead vocalist of the Stranglers in 1990) for ‘Somebody Somewhere’.

A number of local session musicians and backing singers were also brought in to augment the sound, including Alternative Radio’s Rob Fennah and Kevin Roberts, Sylvan Richardson (formerly of Simply Red), Gordon Longworth (who’d worked on Ian McNabb’s debut album, Truth and Beauty), Jill Jones (one-time backing vocalist for Prince) and Jennifer John (who was later credited with vocals on ‘Sometimes’, which featured on OMD’s comeback album, History of Modern, in 2010). “We get the players – and backing singers – to do what we’ve got in mind,” Martin told Music Technology in 1993, “and then ask them to just mess around and do what comes naturally. It doesn’t alter the song, but it brings it to life by altering important little details, things you would never have thought of.”

For the esoteric ‘Photograph of You’ (which originally started out as a jingle idea), the band wanted to include Harry Dean Stanton’s voice – as featured in Wim Wenders’ acclaimed road movie, Paris, Texas – but the character actor refused permission, so the spoken word part was replicated by the actor Simon Dutton, who is perhaps best remembered for playing Simon Templar in an 80s revival of the TV series, The Saint.

OIL SPILL

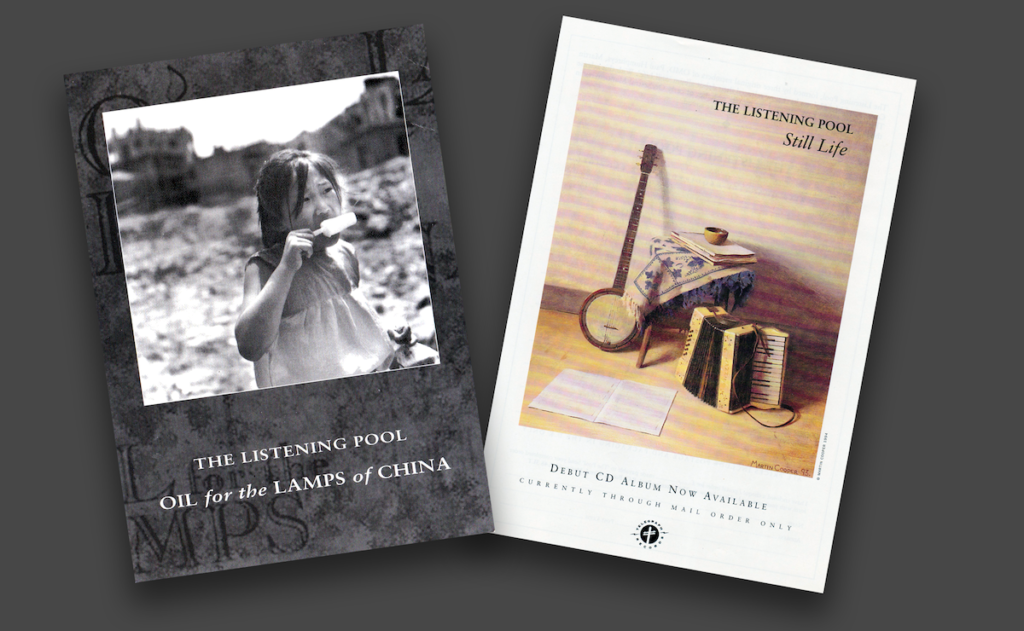

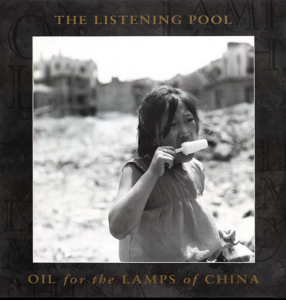

The bulk of the album was recorded at Paul’s home studio – christened The Rhythm Ranch – with the band self-producing. Although they’d kept in touch with Stephen Hague – who’d helmed both Crush (1985) and The Pacific Age (1986) – the American producer couldn’t offer anything more than moral support due to his limited availability (he was working on New Order’s Republic album at the time). The band did, however, manage to enlist the services of engineer Tom Lord-Alge, who’d worked with both Hague and OMD, and the Grammy Award winner mixed the band’s debut single, ‘Oil for the Lamps of China’, which shared its name with a book by Alice Tisdale Hobart, published in 1933. The sleeve for the July 1993 release incorporated a striking photo of a Chinese girl eating a lollipop, taken by photographer Clive Vincent Jachnik, a former school friend of Martin’s. “I just bumped into him walking down the street,” he told the Telegraph fanzine that year, “and he said, ‘I’ve a photography exhibition on next week, come and have a look’, so we went, and, for some reason, this particular one just seemed very appropriate.”

Although it’s arguable that this mid-tempo number wasn’t the perfect song to launch the Listening Pool’s career with, it did receive a very favourable review in the music industry’s trade magazine, Music Week. “This is a likeable, quirky and commercial song that is more faithful to the trio’s OMD roots than the current single [‘Dream of Me’] by Andy McCluskey, who alone carries the torch for the group now,” wrote Alan Jones. “Had it been released as an OMD single, it may have made the Top 40, and still might. Either way, it’s well worth stocking.” In the end, however, the single didn’t chart. The band did have a deal in place with BMG to distribute both the single and subsequent album, but there was little left in the coffers for marketing (there was no promotional video, for instance) – Paul later admitted that, although he’d pumped a lot of his own money into the label, he felt obligated to utilise any spare funds for Telegraph Records’ other acts.

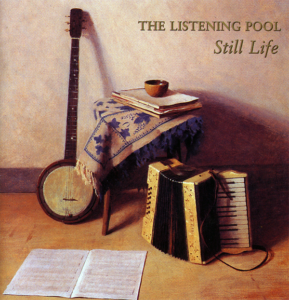

FRANK’S BANJO

Originally pencilled in for a September 1993 release, the 11-track version of Still Life eventually arrived in the spring of 1994, initially by mail order only. Understandably, OMD’s fan base was targeted, and there was an opportunity to purchase a signed album and a print of ‘Frank’s Banjo’, a painting of Martin’s that was used on the front cover of the album. A retail version of the album, which included ‘Photograph of You’, was released later in the year, but the lack of a hit single, coupled with limited advertising, ensured that sales were slight. Although there were some positive reviews of the album, the marketing campaign wouldn’t have been helped by Ian Cranna’s brutal one-star review in Q magazine: “The lyrics are awkward adolescent poetry with little to catch the imagination, and the whole thing is polite to the point of dullness… More still than life, they desperately need energy, ideas and a decent singer.”

In spite of its mixed reviews, there’s plenty to admire about Still Life and, a quarter of a century on, it stands up remarkably well against the somewhat dated dance-pop sounds of Andy’s Sugar Tax and Liberator albums. Indeed, since its release, this sophisticated album has drawn favourable comparisons with the likes of the Blue Nile, China Crisis and Talk Talk. But that’s not to say that OMD’s DNA isn’t prevalent on this slow grower. Tracks such as ‘Meant To Be’ (released as the album’s second single), ‘Somebody Somewhere’ and ‘Where Do We Go from Here?’ all bear the melodic hallmarks of the ‘Joan of Arc’ hitmakers, while moodier pieces such as ‘Blue Africa’, ‘Photograph of You’ and the closing instrumental, ‘Hand Me That Universe’, may well have fitted in with the more organic soundscapes of Andy’s under-appreciated OMD album, Universal (1996).

Disappointingly, the funky ‘Golden Years’ and the more groove-based ‘Satellite of Love’ weren’t included, and plans to cut a second record were abandoned when the band decided to go their separate ways, with Telegraph Records folding after just a handful of releases. Martin went on to focus on his art career, while Malcolm remained in the music industry, working with artists such as Dean Johnson and Jo Mooney. Meanwhile, following the collapse of his marriage, Paul teamed up with Propaganda’s Claudia Brücken for some live shows in the US in 2000 and, as OneTwo, released the Item EP (featuring Depeche Mode’s Martin Gore) in 2004.

In 1998, Paul briefly hooked up with Andy to promote The OMD Singles, but it would be several years before the original four-piece line-up would, in the words of the Listening Pool, ‘rediscover the golden years’, reuniting to play OMD’s magnum opus, Architecture & Morality, in full in 2007, paving the way for an exciting new era in this legendary outfit’s fascinating history.

Copies of The Listening Pool album Still Life are available via: https://www.malholmes.com/the-listening-pool/

Thanks to Martin Cooper, Malcolm Holmes, Paul Browne and Jan Humphreys.

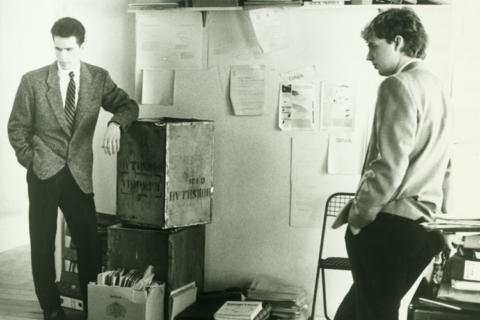

Listening Pool photos: Paul Browne.