“It was two teenagers in somebody’s back room who decided to do it themselves…”

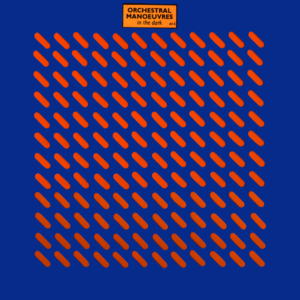

Originally released in 1980, OMD’s debut album Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark featured some of the most iconic OMD songs, including ‘Electricity’, ‘Bunker Soldiers’ and ‘Messages’. The sleeve design (by Peter Saville and Ben Kelly) for the album was built around a die-cut concept that also marked it out as an instant design classic.

In 2003 the album was reissued featuring remastered tracks taken from the original master tapes for the album. The reissue also boasted bonus tracks along with sleeve notes, photos and restored artwork. As part of the process of penning the sleeve notes, Paul Browne interviewed the band to collect their thoughts on Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark as an album then and now.

What do you recall about the ideas and emotions that originally inspired the songs on Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark?

Well of course the first album was basically the songs that Paul Humphreys and I had been writing from the age of 16 until we signed to DinDisc records. So really it was a four year collection of songs spanning from the very first actual song we wrote when we got a tuned keyboard, ‘Electricity’, right through to… I think the last song that we actually wrote for the first album was ‘Pretending To See The Future’ which was actually written about signing a record contract. I was already being cynical about the music industry even then!

And of course in-between you’ve got songs that came from the days of The Id, things like ‘Julia’s Song’, which gets its name from the fact that it was a song that Julia Kneale actually wrote the words for – and used to sing when The Id was an 8-piece band. And also from The Id era there was Electricity’. I think ‘Red Frame/White Light’ was an Id song, but we never recorded it. So there were songs that were slowly collected and polished over a period of 4 years.

Were you happy with the final album?

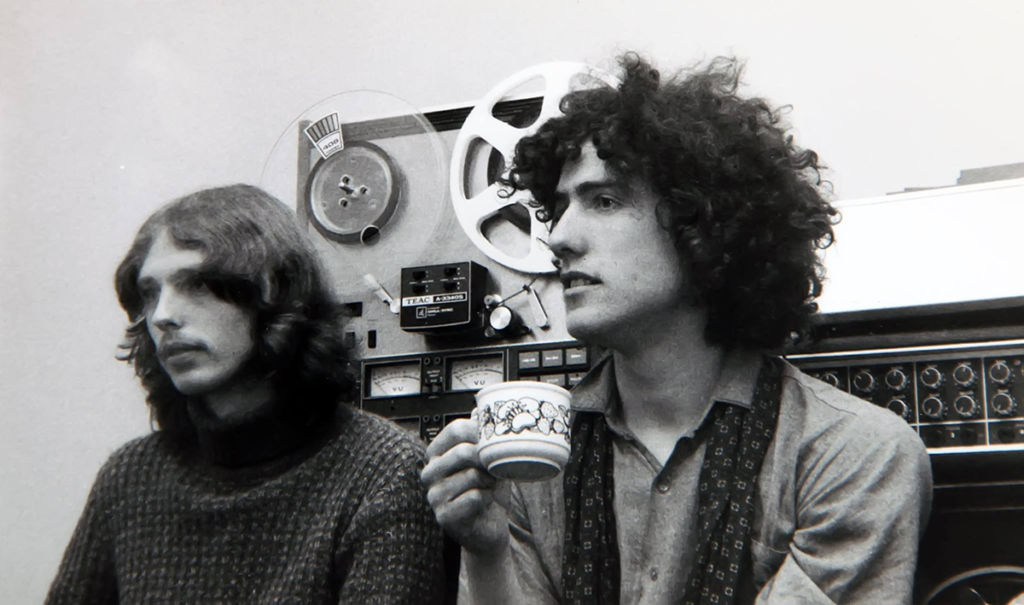

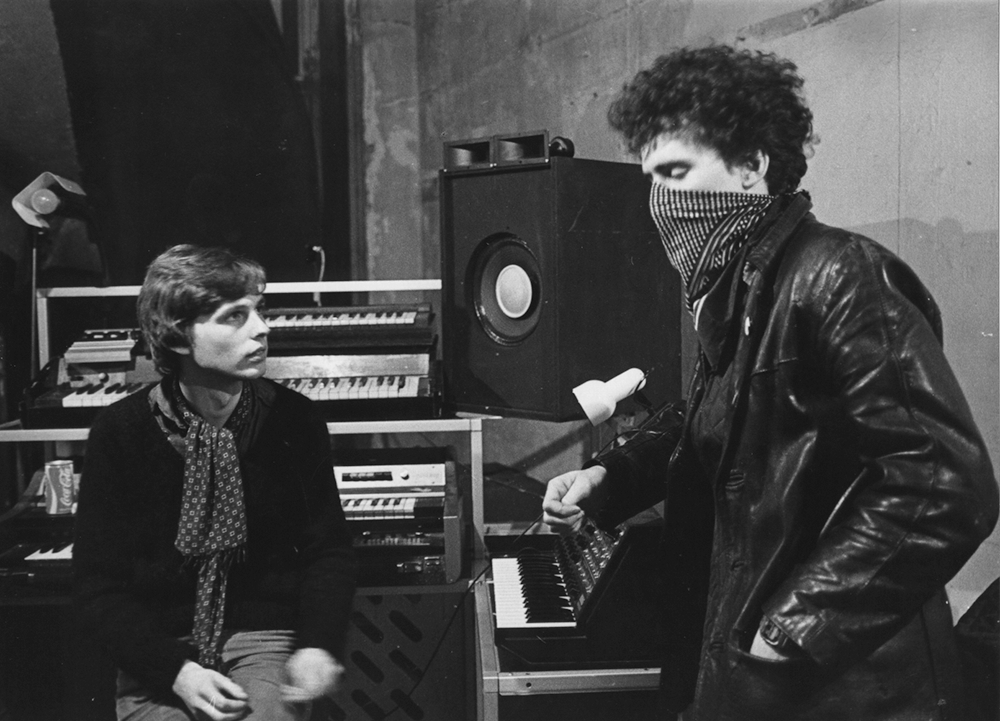

I’m happy with the songs, but the second we finished the recording of the album I think I realised that the actual quality of the recordings was pretty primitive. Because we could not believe that we’d been signed to a major record deal we still, at that point, did not think of ourselves as a commercial band, that we could be perceived as writing pop songs that would sell in any large numbers. So rather than take the money and spend it on recording in somebody else’s studio, we took the money and built our own studio. Effectively budgeting for failure, making the assumption that “Well no one will buy the record and if we get dropped at least we’ve got our own studio to continue our hobby”.

Because effectively that’s what OMD was at that point – a hobby. We didn’t take it seriously as an opportunity to be hit songwriters. So we built The Gramophone Suite in the abandoned upstairs floor above a music shop where we bought all our equipment in Liverpool.

Essentially, I think the studio took three weeks to build and we recorded the album in three weeks. So both the studio and the recording were very hastily thrown together and I think the album shows that. Its actual recording quality is pretty poor. But, conversely, it has a charm and a naivety which captures a moment very specifically.

How did it feel signing to DinDisc?

I think we were amazed. In the summer of ’79 we still couldn’t believe that Factory Records had wanted to release our first single ‘Electricity’ and although obviously that had done well, and we’d been asked to support Gary Numan on his tour in the Autumn of ’79, we didn’t still really take the whole of the music industry terribly seriously. We just couldn’t believe that doors kept opening for us without us even trying to request entry. And signing to DinDisc just seemed to be another, to us, lucky break.

I mean maybe we were naive, maybe we didn’t realise some of the negotiations that were going on in the background but I think we just thought that they were wonderfully mad to sign us and they were going to regret it, but we were going to enjoy it whilst it lasted!

Can you explain a little about why you were dissatisfied with issuing the album version of ‘Messages’?

Well, as I explained, the first album was recorded in our own studio very hastily and sounds like it. ‘Messages’ – and its B-side ‘Waiting For The Man’ – were recorded in London. And to be honest, although DinDisc obviously thought we had potential, they put us in a studio in London on an overnight downtime rate so that we were actually working from midnight until 10 o’clock in the morning – and sleeping during the day on one of Richard Branson’s houseboats on one of the canals in Little Italy in Maida Vale.

So I think essentially, after ‘Electricity’ had been released then ‘Red Frame’ had been released then ‘Electricity’ had been re-released, very possibly – although the first album had sold reasonably well – DinDisc thought it was time for a change, that possibly we couldn’t be trusted to actually produce ourselves because the songs didn’t quite sound professional enough. So it was time to wheel in the producer and being nice polite boys we agreed to give it a go.

As I recall, we were booked into Advision Studios with Mike Howlett – the first time we had worked with an outside producer – and I can’t remember whether we recorded in one day and then mixed in the other or we tried to record and mix in one day. But I know that we started upstairs and we then we mixed downstairs and I know we that went right through the night on the mixing. I can’t believe we did it all in one day, but I know that we mixed right though until 1 o’clock the next day. That was the first day-through-night sort of 24 hour session I had in a recording studio.

And I also remember at the time that yet again, and this was something that was to haunt me for my entire recording career, I just had no objectivity about the finished mix and I just didn’t like it because it didn’t contain certain elements that I thought I wanted to hear and it contained other elements that I knew were suggested by the producer that ultimately took me a long time to get to like. And to be honest, ‘Messages’ was the first example of a song that was a hit that even whilst I was standing on the stage of TV studios presenting it, I was thinking to myself “God, I really don’t like this mix, I’d like to change it!” (laughs)

Peter Saville’s final album design is a stunning piece of work. Did you have any ideas yourself about potential design ideas?

No. To be perfectly honest, by that stage I’d already realised that Peter Saville had better ideas about sleeve design than myself. As you know, we’d first met him while we were on Factory and we were very pleasantly surprised when, completely independently of us, he’d pitched up as the in-house art director at DinDisc records where we’d gone and signed.

The first album, essentially, was a Peter Saville design based on a Ben Kelly idea. As I recall, I think, Peter Saville was having a conversation with Ben about what he should do for the first album and he wanted to do a hi-tech sleeve and Ben Kelly just told him to go and have a look at the door in a shop in Covent Garden that Ben had designed. And it was just a grille, it was a punctured metal grille with diagonal lozenges in it. And that was it.

Peter got the idea and did it in very bold colours – he did it in that sort of bright turquoise blue and persuaded us to have an inner sleeve of bright orange that you could see through these punched lozenges. And of course it became an award-winning sleeve. I’m sure that the album probably sold many thousands because its sleeve was so distinctive. People just looked at this sleeve and said “Wow! What is this? I’m going to buy this and find out what it is!” (laughs)

The only dilemma for us, of course, was that not understanding how the royalty system worked, we had a sleeve that was costing us so much to manufacture that for every record we sold we were barely earning a penny! (laughs)

That sounds not unlike the story of Peter Saville’s design for the 12″ of New Order’s ‘Blue Monday’ where they were losing money for every record they sold!

Yeah, I mean the dilemma is that people bandy words around like “packaging deduction” which you just don’t really think about. You just say “Well I love the sleeve, I don’t care, let’s have the sleeve” and people say “Well you only earn so many pence per album and this sleeve is actually costing 5p more than the average sleeve and it’s being deducted against your royalties because you requested it”. Ultimately, that was why we stopped using the first sleeve because when the penny finally dropped, that it was costing us so much money to manufacture, then… and it’s typical isn’t it, the record company were delighted with an award-winning sleeve that was almost selling itself, but it was the band that were paying for it! (laughs)

How do you feel about the album today? Do you think that it stands up to the test of time?

Well now that I’ve got over the frustration of the fact that it did sound rather amateur and badly recorded, it’s a rather charming snapshot of the period in time that was, essentially, although it was released in early 1980, it was punk synths. It was two teenagers in somebody’s back room who decided to do it themselves and were playing with the most ridiculously cheap load of second-hand equipment and playing with self-taught knowledge – one-fingered melodies and simple primary chord structures. I find it a very charming and endearing first step into my career now, in hindsight. At the time, I was disappointed that my four years of adult work had ended up sounding a little bit cheap! (laughs)

When you see it now in the timeline of the 80s years of OMD it is a wonderful, wonderful na’ve first album. But that’s because we went on to do Organisation, Architecture & Morality and all the various other things. I mean one of the things about OMD which I think is great is this amazing journey, this roller-coaster ride. Every album is very distinctive – they all sound totally different to each another which, I think – for better or for worse, and some of it is for worse! – is a testament to our determination to keep going somewhere!

Original interview by Paul Browne 2003

Revised text 22nd February 2020