“If I had a complaint about Sugar Tax it was that there was nothing weird on it, so I thought this one would be edgier. But I seem to have written my poppiest album ever – even if, as usual, the lyrics are a bit dark” – Andy McCluskey

With the success of the Sugar Tax album, which marked OMD’s first studio album for nearly five years, Andy McCluskey had swiftly returned to the studio in the post-tour months to capitalise on the resurgence of interest in OMD. But the road to that point had been one of many twists and turns with a fair share of rough ground. Sugar Tax also marked the first album in the post-split years, when Andy had parted company with Paul Humphreys. These post-split years had been tough for Andy who had been used to working with Paul since his teenage years. As a result, many of the songs that he composed during this period would reflect this frustration with often quite personal aspects in the lyrics.

That background also contributed to a crisis of confidence at the heart of Sugar Tax, which is evident from the minimal presence of Andy in both photographs and credits in the liner notes. Preferring to hide behind the banner of OMD as a name, he had also collaborated with new, younger musicians to give this new OMD a more modern style.

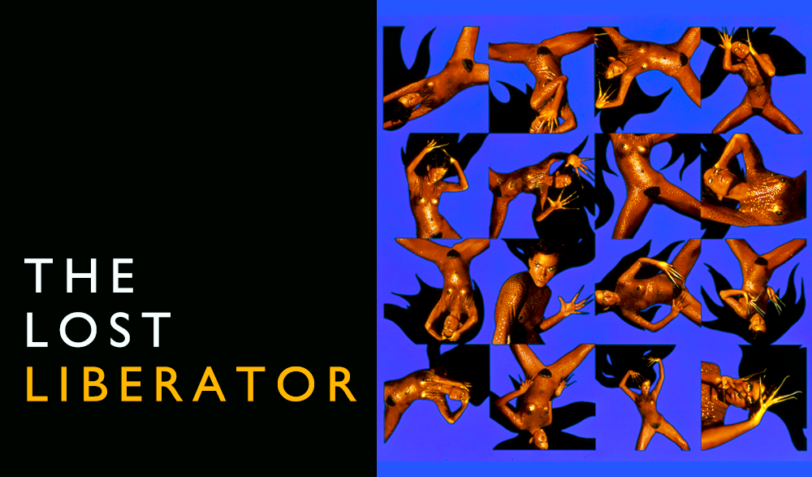

But the Sugar Tax’s success had reasserted Andy’s confidence – and it had also triggered a desire to explore more weirder directions, something which had been a part of OMD’s previous legacy (for better or worse) in the years before. An analysis of Liberator as an album (see Barry Page’s extensive overview) explores the 1993 release as it stands in OMD’s catalogue, but there was originally a point where Liberator’s trajectory took it in a slightly different direction.

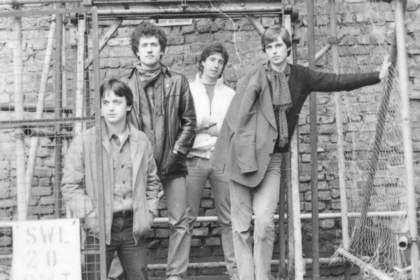

To explore this alternative history, it’s necessary to wind back to the early 1980s in a time where Architecture & Morality (the album that was to cement OMD’s reputation as an electronic band) was still on the horizon. While the band’s interest in brooding, melancholic tones had been evident in earlier compositions (particularly on the Organisation album) it didn’t really become overt until Architecture & Morality. Here, an interest in choral elements and often otherworldly sounds become very overt – and would also become part of OMD’s DNA going forward.

OMD’s interest in choral elements in music composition had originally been sparked by a chance meeting with Dave Hughes, a local musician who had previously performed with OMD during their initial OMITD album tour (you can see Hughes in the promo video for ‘Messages’). Hughes was already exploring his own musical ventures, which offered a more baroque take on electronic music (this project was later named Godot and provided an intriguing counterpoint to OMD’s more direct synth-pop direction). .

Part of this exploration had involved working with tape loops of a choir tuning up. Each tape loop had a single sung note which were then transferred onto a 16-track tape recorder. It meant that individual notes could be brought in and out using the mixer, creating an oddly hypnotic sound. In essence, it was like a crude Mellotron – a keyboard-based instrument that runs tape loops (and an instrument the band would later use on ‘Maid Of Orleans’). Paul Humphreys and Martin Cooper went to work composing an abstract idea from this foundation, which was given the working title of ‘Choir Song’. The composition was later retitled ‘Souvenir’ and the rest is history.

Andy McCluskey took this interest in choral music (and its roots in religious music) forward for penning songs such as ‘Joan Of Arc’. It gave Architecture & Morality a very distinctive sound profile and the logical direction following the album’s success would have been doing Architecture & Morality II. But for Andy and Paul, who had always been keen not to craft a ‘do-over’ of any previous OMD album, the idea was distinctly unwelcome. As a result, they conjured up the Dazzle Ships album the following year – an album which certainly didn’t replicate Architecture & Morality, although at the time they may have regretted that decision!

While the band dabbled with sampling techniques and ideas on a few of the post-Architecture & Morality albums, by the time of The Pacific Age they had arguably strayed far from the elements that had brought their initial success. With the subsequent splitting of OMD, it also suggested that the OMD story had perhaps reached its end.

But by the time Sugar Tax was starting to be written and produced, Andy was once again peering into the well of inspiration – which included bringing back the choral tradition to OMD songs. He was also keen to bring back that particular feeling of melancholia that had been a vital part of many of the band’s classic compositions.

Andy’s interest in choral music had never gone away and he had a keen ear for recorded works – particularly works that drew on the religious legacy of the choral tradition. This is why the sober tones of ‘Walk Tall’ (from Sugar Tax) are made more robust by the sampling of a recording of ‘Miserere’, a traditional choral piece by Allegri.

Equally, tracks such as ‘All That Glitters’ took on a more brooding aspect compared to the dancepop that Sugar Tax employed on its many singles. These were just nods in a certain direction, but when the initial songwriting sessions for Liberator were underway, it was a direction that Andy was initially keen to explore. As with Sugar Tax, Stu Kershaw brought his own talents to bear on assembling the new compositions for its follow-up. A lot of the brooding tone of these songs came through Stu’s own ability to write and compose (it’s no surprise that ‘Walk Tall’ and ‘All That Glitters’ have his particular touches).

But as an album, Liberator went through a lot of changes, adjustments and restructuring – even in terms of its original visual style and themes. Originally, the album’s title had been inspired by Andy’s interest in World War II aircraft (a theme that was a constant in OMD’s history – see our article OMD And The Art Of War) with his personal favourite, the B24 Liberator, being the chief inspiration. But the album’s focus had been more drawn from the nose cone art that flight personnel had painted on their planes as a morale booster. “I think that the original idea of the ‘Bomber Girl’ was a starting point” Andy commented in the fanzine Telegraph at the time, “but the more I thought about it, the more I was concerned that quite simply it was too old fashioned. You couldn’t copy a Vargas-style Bomber Girl, it’s all been seen before 50 years ago, what relevance has it to the 90s?”

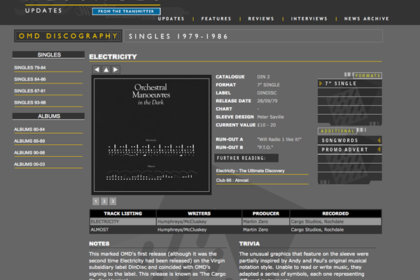

At the same time, the large number of potential songs (estimated at around 30+ compositions) had meant that there were some culling to do as the album trundled on. This included ‘Liberator’ (referred to then as ‘The Liberator’) – a song that had apparently first been conceived back in 1985. “It’s potentially a really good song” Andy remarked at the time, “I just haven’t got around to finding a way of doing it which will be really great.” In fact, ‘Liberator’ wouldn’t see the light of day until 2019 as part of the Souvenir box set’s unreleased material archive.

Meanwhile, Andy’s interest in choral music would come to bear on some of Liberator’s initial short list of contenders. ‘Agnus Dei’, which was one of Andy’s nods to the weirder, edgier direction he was keen on (and also the first song penned for the album), had drawn inspiration from one of the CDs that he had on regular rotation.

In this case, Cathedral Music by Christopher Tye, which collated a lot of Renaissance-period compositions by the obscure composer. Tye rose to prominence in the 16th Century as the music teacher of Edward VI, but was also well regarded for his choral and chamber music compositions. Cathedral Music was a collation of some of his work recorded by Winchester Cathedral Choir and released in 1991.

Andy pulled two of the works from that CD to use as the base for two new compositions, including his ‘choral rave’ outing. The first of these was ‘Agnus Dei IV’ (part of the Mass Euge Bone sequence on the Tye CD). Andy had been so taken by this piece that he rearranged his own ‘Agnus Dei’ so that the chords follow the original more closely.

‘Agnus Dei’ also utilises another sample, this one culled from Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares (‘The Mystery of Bulgarian Voices’), a compilation of traditional Bulgarian folk (songs that 4AD label founder Ivo Watts-Russell had been so taken by, he licensed the release in the UK). ‘Agnus Dei’ samples part of the song ‘Besrodna Nevesta’ taken from the second volume of the series.

The other Tye composition that had made an impact on Andy was ‘Sanctus’ (taken from the same sequence on the Cathedral Music album). This song combined the initial opening bars of the original recording alongside a ‘bouncy’ piano element that tacked closer to the Sugar Tax template of dance pop. You can hear the inspiration for that track on Tye’s ‘Sanctus’ which is still available on CD.

Outside of these new songs, Andy had also looked at composing a song that referenced ‘All That Glitters’ from Sugar Tax. But while ‘All That Glitters’ had a certain stately, melancholic quality to it, ‘Kiss Of Death’ managed to take that ball and keep running with it…

The chord sequence that opens ‘Kiss Of Death’ would send a chill down the spine of even the most jaded listener. This was a big, bold gothic pop number with lyrical couplets that hit straight to the heart:

When you leave as you go

Take my last dying breath

There’s a strength to be found

In this last kiss of death

Many OMD songs have been spawned from earlier raw demos, while others have been combined from two distinct songs. So, both ‘Kiss Of Death’ and ‘Dollar Girl’ share some DNA together, despite being very different in terms of style and delivery. This is mainly evident in the chorus, particularly as both songs have quite long and complicated sequences.

While the running joke was that you could sing the lyrics to ‘Pandora’s Box’ to ‘Dollar Girl’, you could also sing the lyrics to ‘Kiss Of Death’s chorus to ‘Dollar Girl’ – and vice versa! On that basis, one of the songs had to go. Unfortunately it was ‘Kiss Of Death’ – whose fate reflected its own song title.

Elsewhere, inspiration for other songs was coming from stranger directions. In one instance, Andy had been drawn to a haunting story that had appeared in a copy of Life magazine. In 1944, a devastating fire ripped through a circus tent in Connecticut. 168 people died in the tragedy – and some of the bodies were unidentified. One of these victims had been a child who had subsequently been buried in a grave which featured a headstone with her morgue number: Little Miss 1565.

It wasn’t until 40 years later that a detective had decided to re-open the case and tried to discover the identity of ‘Little Miss’. The story of his search was revealed in a long-form feature for Life, a harrowing tale of love and loss that had a profound impact on Andy McCluskey, in much the same way that Joan Of Arc had touched something inside him many years prior. As a result, he worked on a composition with Stu in a bid to capture these evocative themes in a musical style that would do them justice.

BUY NOW

https://amzn.to/4f0Yp7E

Lyrically, Andy sketched out the idea of two people being divided by tragedy. For a while, the track had existed under the title ‘1565’ (a title that had also been considered as a possible album title at one stage) but was later christened ‘Twins’. It was a slow, mournful number that rotated around lines such as “No one loves you like I love you” that delivered an emotional punch.

With all of these potential songs in play, Liberator was shaping up to be a surprisingly bold gothic pop album that embraced OMD’s modern 90s direction, while also acknowledging the strong foundations of its past.

Unfortunately, many of these songs would never grace the finished album. Instead, Liberator went in a different direction that tracked closer to Sugar Tax’s more poppier elements.

In a subsequent article for Telegraph, Andy was quite transparent on developments: “’Twins’ and ‘Kiss Of Death’ didn’t make it on the album, but I’m not using then as B-sides because they’re too good. We didn’t feel ‘Kiss Of Death’ was working as well as the others we’re working. I think there’s a better version I can get but I haven’t got the time to pursue it yet, it needs a bit of taking apart and reworking. But lyrically it’s one of the best songs that I’ve ever written. ‘Twins’, again, musically I don’t think it quite cut it. I’m going to have to look at it a new angle. But this two are too good to throw away on B-sides.”

Some tracks survived the cull, particularly ‘Agnus Dei’ (albeit in a slightly slower version than earlier incarnations) and also ‘Christine’, another bittersweet composition that bears the hallmarks of Stuart Kershaw’s particular talents.

But there’s something missing from the heart of Liberator and although Andy had wanted to push the weirder aspects of Sugar Tax, ironically he ended up removing nearly all the tracks that embodied that ‘gothic dancepop’ direction.

Had Liberator been reconsidered at the time, it’s quite possible that it would have played Organisation to Sugar Tax’s OMITD. It would also mean that some of OMD’s finest ’90s period compositions would have had the chance to shine, perhaps altering the course of OMD’s future as the band’s story (at least for the 1990s) closed with the release of Universal three years later.